By Hadley Arkes | (Source)

In his large nature, Robert Miller, my critical but dear friend, offered some kind words about my political works in the pro-life cause; and he sought also to shelter me from his blows as he loosed his terrible swift sword on Matthew Schmitz. Evidently Schmitz had vexed him for his critique of conservatives’ buying into a stylish form of relativism as an ingenious new strategy in the regulation of “speech.” That strategy has been one of hopeful pragmatism: that we will be able to shelter people like Miller and me from the assaults of the Left if we settle upon a rule, as vacuous as it is simple, that we just forgo any claim to have standards of moral judgment when it comes to judging speech as rightful or assaulting, legitimate or illegitimate.

Like Miller, I am a classic liberal: I think we have a presumptive claim to all dimensions of our freedom, even those not mentioned in the Bill of Rights. But the classical position understood that any instance of “freedom” had to raise the question of the ends to which that freedom was directed, good or bad, rightful or wrongful. The notion of liberty was always attended by the awareness of the distinction between liberty and license. And up until 1971 it was understood even by strong liberals that speech could be rightly restricted at times, for speech could be a vehicle for inflicting serious harms along with any other part of our freedom. Even with the First Amendment, John Marshall could say that anyone who published a libel in this country could be “sued or indicted”—sued in an action for personal damages, or indicted for stirring up tumults in the community, perhaps by inciting attacks on religious minorities.

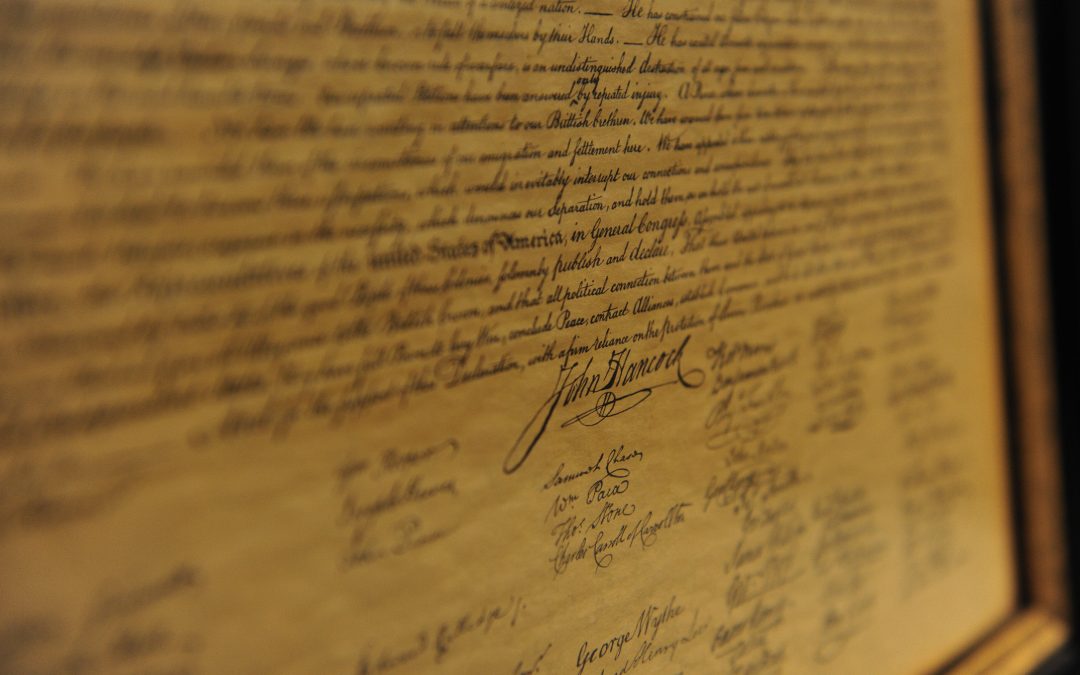

David Hamlin of the American Civil Liberties Union declared years ago that “we must be free to hear the Nazis because we must be free to choose the Nazis.” This was what Lincoln considered the “degradation” of democracy: that it is all form and no substance, that we are free to choose anything—free to choose slavery or genocide—as long as we do it in a democratic way with the vote of a majority. But of course our “freedom to choose” in a free election is based on that underlying principle, “All men are created equal,” and the only rightful governance of human beings must depend on “the consent of the governed.”

The Nazis rejected that principle at the root. To cast a ballot for a Nazi party in an election is to vote to remove that “freedom to choose” from all of those people around us in the adjacent voting booths. A man who respects the moral ground of his own freedom would not claim this right to choose the Nazis in an election. It would be an act of moral incoherence. But we absorb that incoherence in this way: We talk ourselves into the notion that, as far as the law is concerned, we must be free to hear the Nazis, because the ends of the Nazis must be as legitimate to choose as any other set of ends on offer in the landscape of our politics. That is relativism all the way down. And that, I take to be the deep concern that has animated Matthew Schmitz in his recent pieces.

As I understand my friend Robert Miller, he would avert that charge of relativism in this way: He himself harbors no doubts in judging the Nazis or the KKK as pernicious. And he has no doubt that he is affirming a deep good in a state of affairs that forgoes controversial moral judgments in the hope of preserving a vigorous regime of freedom. He finds good reason to hope—or bet—that bad causes will be exposed, that things will work out far better in the long run, if we recede from our natural inclination to make moral judgments about those ends of “speech” and politics that may be rightful or wrongful. He draws on Aristotle to register his own hope that “anyone arguing for the true and good should always be able to prevail in fair debate over someone peddling falsehood and evil doctrines.”

Robert Miller, an urbane man, anchored in the world, is surely as aware as anyone of the demagogues around us, the thuggish partisans of abortion and transgenderism. Their success in our politics gives fresh evidence every day that Miller’s anchoring conviction is but a hope only wishing to be true. His position, in other words, is built on layers of speculation or prudent compromises that hope to produce a decent outcome.

But it is also built on layers of insistence that it is dangerous for us to suppose that we have access to moral truths that would allow us to pronounce on the rightness or wrongness of the ends pursued by the Nazis or white supremacists or anyone else in political life. By the time we have fitted into that of state of mind, we would have removed the moral ground that could explain the rightness or goodness of that very regime of freedom we are trying to preserve. In place of that moral defense in principle, we would simply have a set of utilitarian guesses: that if we pretend we have no standards of judgment, things will work out better for us in the long run. It may be the state of eudaemonia that Robert Miller favors, a state of human flourishing, with a supply of happiness modest enough, decent enough for the likes of us.

In the early days of the Civil War, Lincoln warned about the overly clever positions of certain politicians in the Border States. These were decent men who favored a policy of “armed neutrality.” They would use their arms “to prevent the Union forces passing one way, or the disunion, the other, over their soil.” This would be, said Lincoln, “disunion completed. . . . At a stroke, it would take all the trouble off the hands of secession.” Many of the men who favored this compromise were, he said, “doubtless, loyal citizens,” but nevertheless they were committing “treason in effect.” Robert Miller is no moral relativist, but what he is giving us is a utilitarian scheme, with a pyramid of hopeful speculations, covering over layers of relativism. We might say that it is “operational relativism,” or relativism in effect, even if it is covered over with a fig leaf of confidence in a benign, good outcome.

As he sought to separate me from his criticisms of Schmitz, Miller gave a helpful, accurate account of a good part of my argument: “Arkes does not think that non-insulting, non-profane reasoned discourse, no matter how immoral the positions advanced, may be suppressed.” What Miller was referring to was the understanding I have been trying to preserve from the classic Chaplinsky case of 1942 on assaulting or “fighting” words.

As Justice Murphy said in his opinion, we can be more justified in barring certain assaulting words and gestures because they were “no necessary part of any exposition of ideas.” Mr. Rosenfeld, in New Jersey, could be asked to stop wrecking the climate of discussion at a meeting of the school board with his persistent, one adjective, “motherf—ng.” That is, he could be restrained in that way without barring him from giving the most searing, substantive critique of the school board. And, as Miller knows, I’ve argued that those self-styled Nazis, marching through a community of survivors of the Holocaust in Skokie, Illinois, could be barred from carrying out that gratuitous act of wounding. But we could restrain them without barring the publication of Hitler’s Mein Kampf or any other racist tract, put down in the cooler format of writing.

Robert Miller seems not to have noticed, though, that Justice Alito had indeed picked up and incorporated that part of my argument in the recent Iancu case on obscene words in the titles of corporations. There was some irony then in Miller’s observation that “Justice Alito has rejected Arkes’s reading of the relevant cases.” Whether strictly right or wrong, Miller surely could not take that observation as one that confirms the wrongness of my position. Justices Blackmun and Kennedy had clearly rejected Miller’s position on abortion, and I would never have taken that as proof that Miller had been refuted. I might be charged here, rather, with the fault of failing to rescue my friend, the justice, from falling fully into the currents of relativism that were luring his other conservative colleagues.

Miller does not mention the deeper irony in saying that Justice Alito had rejected my “reading of the relevant cases.” The most relevant cases here happen to be the cases in which Alito himself had stood alone, in singular dissent from his colleagues. And while standing alone he was still holding to the position that I have been seeking over the years to defend. He was the only one, then, to insist in the classic vein that our vaunted “freedom of speech” under the First Amendment did not protect the freedom of the Rev. Phelps and his gang to harass the funeral of a dead Marine with signs saying “Semper Fi Fags” and “Thank God for Dead Soldiers.” He was also in lone dissent as the Court draped the protections of the Constitution around video games he described in this way:

The objective of one game is to rape a mother and her daughters; in another, the goal is to rape Native American women. There is a game in which players engage in “ethnic cleansing” and can choose to gun down African-Americans, Latinos, or Jews. In still another game, players attempt to fire a rifle shot into the head of President Kennedy as his motorcade passes by the Texas School Book Depository.

At a certain point, the currents of relativism carrying his other colleagues on the Court seemed finally to beckon him as well. And in part he might have engaged in the same kind of reckoning that Robert Miller suggests: The drive of the Left to brand their opponents for hate speech at every turn, on matters of marriage and the transgendered, may stir cautious people into seeking safe harbors. The center of the argument among conservatives is whether safety will truly be found in a doctrine of relativism or whether that move will simply give up the moral ground on which the conservatives could still summon a defense of their positions. For my own part, I haven’t given up the challenge of entreating the magnificent dissenter in the Phelps case to reclaim his former position, so forcefully expounded. And if I can bring him back, who knows? One day I may bring over Robert Miller as well. He remains the dearest of friends, even in the presence of disagreement; for he is the source of penetrating arguments, and he persistently gives me reason to think anew.

——

If you found this blog post of interest, you might want to explore these Thinker Education courses:

- Do Free Markets Promote Cooperation?

- Does Capitalism Hurt the Poor?

- Was America Established As a Christian Nation?

For this third party post in its full context, please go to:

Classical Liberalism against Relativism

© 2020. Public Discourse.