By Amanda Patchin | (Source)

We wade through a torrent of words and images every day, and yet we mostly lack a clear understanding of what language is and can be for the human. The Catholic philosopher Josef Pieper’s slender little pamphlet Abuse of Language, Abuse of Power, first published in 1974, provides welcome clarity on this issue for we residents of the language-intense 21st century. While Pieper does not delve deeply into philosophy of language, he does clearly and directly address the relationship between words, truth, and persons. That triune relationship is possibly as broken as it has ever been. Pieper offers no direct solution, but his framing of the problem is the proper starting point for any such attempt.

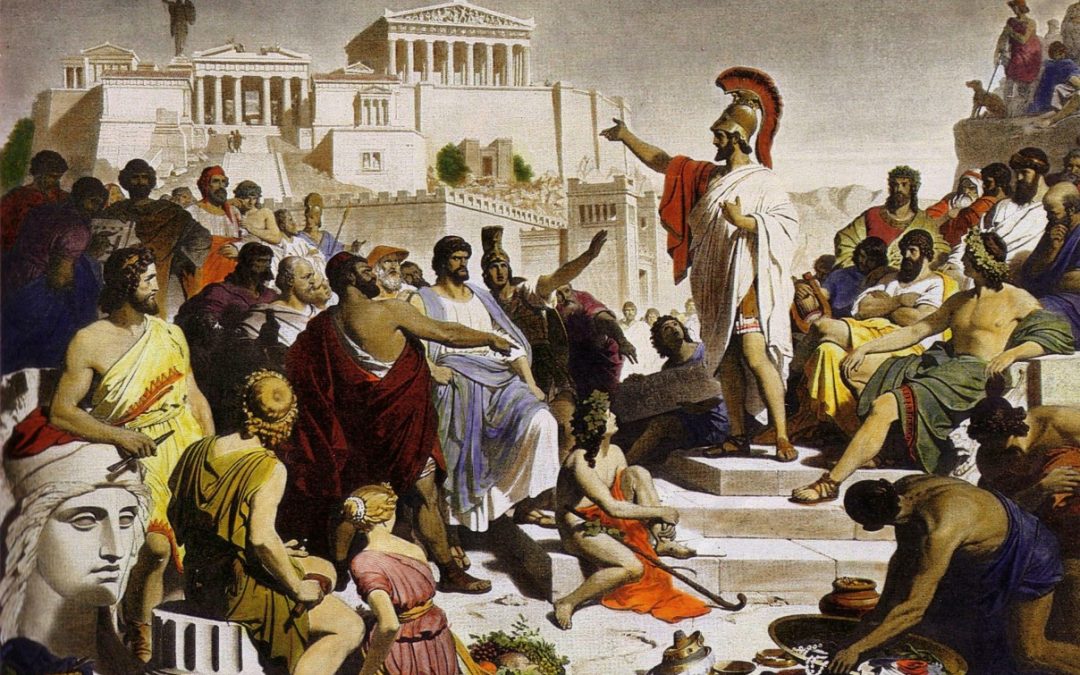

As with much of his work, Abuse of Language, Abuse of Power deals with Platonic philosophy. Pieper begins by asking why Plato was so concerned with the Sophists. Why be worried about people who are attempting to speak in a refined and cultivated way? Plato asserted that the Sophists were dangerous in two respects. The first seems quaint in an age which monetizes everything: money and the work of the mind are incommensurable and the Sophists’ lecture pricing scheme dishonored the distinction between a wage and an honorarium, paradoxically devaluing wisdom by setting a price for words.

The second danger of sophistry is more complex. Plato saw the Sophists corrupting the word. Because words convey reality, any indifference to truth is a distortion of and a corruption of reality.

Pieper then argues that words identify reality to a someone. Communication requires not just a speaker, but a hearer also and by its very nature communication acknowledges the other as a person. Again, any indifference to truth not only corrupts reality but by failing as communication also denies the personhood of the other:

Whoever speaks to another person—not simply, we presume, in spontaneous conversation but using well-considered words, and whoever in so doing is explicitly not committed to the truth—whoever, in other words, is in this guided by something other than the truth—such a person, from that moment on, no longer considers the other as partner, as equal. In fact, he no longer respects the other as a human person (21).

Thus, Plato’s concern about the Sophists is a concern for all human societies. Preoccupation with form over content transforms words from communication between persons into an instrument of power exerted by a person over one he regards as a non-person.

Pieper goes on to distinguish lying (mis-representing reality) from flattery (having any motive in speech other than aiming at truth), and it is this distinction I find most compelling. Lying as a tool of exploitation—understood in the context of political propaganda—is an obvious evil whose destruction is evident all around us. Flattery is a subtler evil whose insinuations debase our humanity while leaving us externally intact. Lying is the characteristic sin of Big Brother in Orwell’s 1984, and flattery is the characteristic sin of Brave New World. Any words that are spoken with the goal of achieving some end other than the communication of truth are flattery—even if they are actually true! The truth-content of the words is not the only component denoting their status as rightly-used language or wrongly-used language. Any abuse of words that debases their truthfulness or their intentions is, for Pieper, an “abuse.”

In advertisements, “the word is perverted and debased to become . . . a drug” and it is used to “propagate a dream world . . . by glorifying human weaknesses” and all of this is effected so smoothly that it really “should make us stop and think [because of] the ease with which we buy all this—buy it in both meanings of the word.” Further, we want our weakness “flattered” by the entertainment industry (what a name for what a business!), not just the advertisements we see. Not just in sensuality, although we love to have our sexual lusts indulged, but in greed and also in “vicious enjoyment of others’ misfortune.”

It is astonishing to me that Pieper could have written that phrase “vicious enjoyment of others’ misfortune” before bored hyper-moderns came up with Hoarders, The Biggest Loser, or the long list of other “reality” television shows too wearisome to list. Worse, Pieper diagnosed the cancerous nature of such “flattery” in 1974 and yet we go on injecting it into our minds and into our souls. Socrates’ recognition of the Sophists’ devious insight—“you are truly experts in this; you must have a deep understanding of human nature; you know exactly which spot to hit”—is trebly apt when applied to entertainment and advertising firms who have studied psychology with the express purpose of pitching every show, every commercial, every publication directly into the strike zone of cognitive biases, emotional needs, and characteristic vices.

Inescapably, Pieper calls the reader to recognize the fundamental breakdown of lying and flattery: all communication ceases when they are employed. Communication can only happen between persons and the employment of falsehood and flattery can only happen when the speaker has ceased to see the other as a person. Pieper has sharp words for advertising and they are even sharper when we apply them to this anesthetized, entertainment-drunk, media-bloated contemporary world, but his final cautions are perhaps a bit more personal. The border between communication and flattery is hazy and even philosophy or theology can be degraded into non-communication if it is “courting favor to win success.” Any sort of success can be the ulterior motive that transforms a book, a play, an essay, a book review, into flattery. It may only be the “success” of being in some unimportant little group but the lure of the “Inner-Ring,” as C.S. Lewis warned, is profoundly enticing.

We have, as Pieper notes, entered a world where we no longer aim at truth in our communication, but instead have been “taken over by pseudorealities whose fictitious nature threatens to become indiscernible” and people have become “satisfied with deception and trickery” and “with a fictitious reality created by design through the abuse of language.” We need the corrective Plato and Pieper offer us. We need “to perceive . . . all things as they really are and to live and act according to this truth,” and we need to understand, deeply understand, that “all men are nurtured, first and foremost, by the truth . . . everybody who yearns to live as a true human being depends on this nourishment,” and we need to cultivate “interpersonal communication” as “the natural habitat of truth.” If we can live according to this understanding of language, we can live as a community habituated to truth and dedicated to the “bonum commune.”

——

If you found this blog post of interest, you might want to explore these Thinker Education courses:

For this third party post in its full context, please go to:

© 2019. Front Porch Republic.