By Richard L. Cravatts | (Source)

The death of a black man under the knee of a brutal police officer in Minneapolis sent shock waves of racial guilt throughout America. Protestors, led principally by Black Lives Matter, took to the streets to malign America’s troubled history with race and reignite the conversation about how to atone and pay for the country’s original sin of slavery and racial oppression. Not surprisingly, that same paroxysm of indignation immediately appeared on university campuses, which for decades have obsessed over and condemned what they perceive to be “structural racism,” a lack of sufficient “inclusion and diversity,” and both subtle and overt instances of racism that offended minority students and supposedly hindered their attaining equity.

Even though a university campus is an unlikely place to encounter actual racism, from the moment they step foot on campus, students are tutored on how, even at some of the most elite educational institutions in the world, they are oppressed, victims of bigotry, hindered by “systematic and structural racism,” and even subject to unconscious, invisible, and latent “racism.” As if to confirm that universities remain petri dishes of racism, virtually every institution has set up fiefdoms of “diversity, equity, and inclusion” offices dedicated to ferreting out any incidence of racism, bigotry, or bias and helping minority students to see themselves as perpetual victims of both real and imagined racism.

Leading the way in this relentless war on ever-present racism, Princeton’s Vice Provost for Institutional Equity and Diversity leads a bloated and costly army of social justice warriors, which includes a Senior Associate Director for Institutional Diversity and Inclusion, an Assistant Director for Equity Compliance, an Equity and Diversity Specialist, and a Director for Institutional Equity and EEO, not to mention three University Investigators mandated, one would assume, to seek out bigotry and oppression on campus.

Given the enormous human and financial capital already dedicated to monitoring and mediating bias and racism, it is curious why on July 4th, some 400 Princeton faculty signed a “Faculty Letter” to President Eisgruber, select administrators, and members of the Princeton Cabinet in which they presented a number of demands and recommendations, calling “upon the University to take immediate concrete and material steps to openly and publicly acknowledge the way that anti-Black racism, and racism of any stripe, continue to thrive on its campus. We call upon the administration to block the mechanisms that have allowed systemic racism to work, visibly and invisibly, in Princeton’s operations [emphasis added].”

In order to create this brave new anti-racist world at Princeton, the long-form faculty letter presents an extensive list of demands, including the predictable ones, such as giving a place at the “decision-making table to people of color who are actively anti-racist and inclusive in their practices”; implementing “administration- and faculty-wide training that is specifically anti-racist in emphasis”; and not only enforcing “repercussions (as in, no hires) for departments that show no progress in appointing faculty of color,” but also requiring “anti-bias training for all faculty participating in faculty searches.”

These types of demands are not atypical of the steps students and faculty often try to implement when addressing perceived racial inequity on their campuses. What was more troubling about the faculty letter, however, was the odious demand that Princeton form “a committee composed entirely of faculty that would oversee the investigation and discipline of racist behaviors, incidents, research, and publication on the part of faculty, following a protocol for grievance and appeal to be spelled out in Rules and Procedures of the Faculty.” Additionally, the letter expects that “Guidelines on what counts as racist behavior, incidents, research, and publication will be authored by a faculty committee for incorporation into the same set of rules and procedures.”

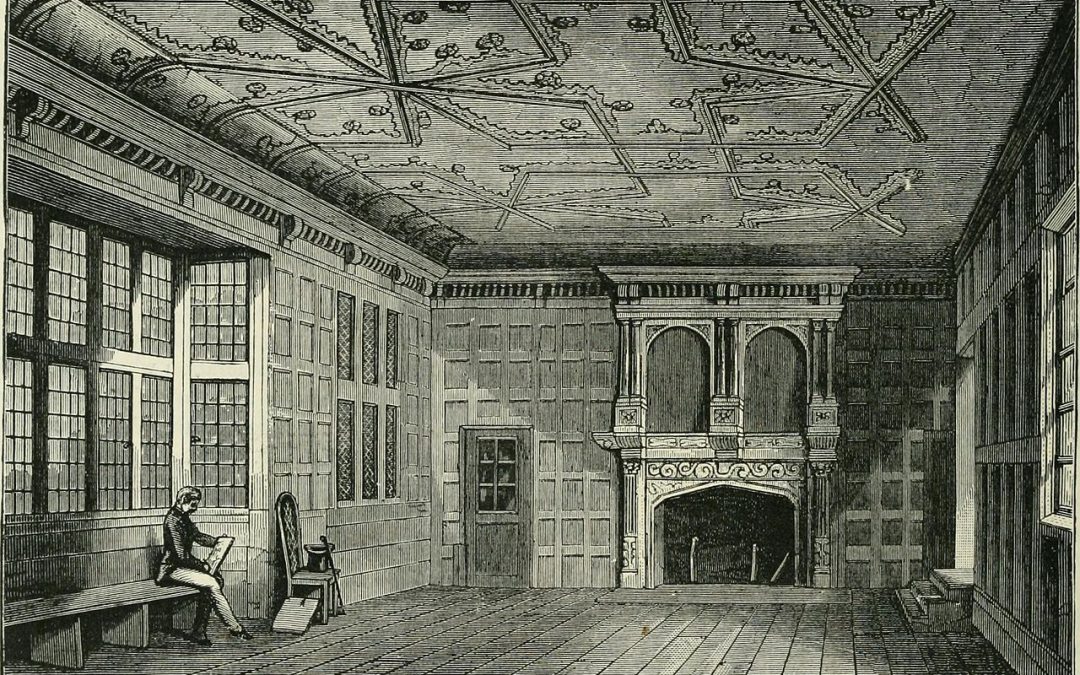

The hundreds of Princeton faculty members who signed this letter either did not fully comprehend what they were proposing, or they conveniently overlooked the fact that what they were calling for was a veritable star chamber, in which a handful of virtue-signaling, race-obsessed faculty would use their own bias and subjectivity to vet the research and teaching of fellow faculty, deciding which viewpoints would be permitted and which, henceforth, would not—a blatant violation of both the spirit and intent of academic freedom.

This proposal is a breathtaking display of pretentiousness and audacity by these Princeton professors, who are confident that they alone can decide which ideas can be taught or written about and which can, and should, be suppressed—all in the name of protecting the sensibilities of student victim groups and, presumably, of creating an anti-racist campus. That is a dangerous notion and one that contradicts the primary goal of the university: the unfettered exchange of diverse views in the “marketplace of ideas.” It assumes, falsely, that some ideas are intrinsically superior to others and that only those deserve to be expressed; that these self-selected professors have the knowledge and insight—about all areas of inquiry—to be able to assess the value of other faculty members’ intellectual contributions, based on what may well be a cursory evaluation of their research and writing; and that, ironically, the massive anti-bias administrative hierarchy that already exists at Princeton is apparently inadequate in eliminating bias and racism at the university and requires further faculty input.

The more outrageous aspect of this proposed committee is that, as the letter reads, it “would oversee the investigation and discipline of racist behaviors, incidents, research, and publication”—in other words, if the faculty star chamber decides that another professor’s views are unacceptably “racist,” there would not only be an investigative process but apparently also the prospect of disciplinary action—punishment for one’s views.

The notion that a committee of faculty ideologues can determine what views about race may or may not be expressed on a particular campus is not only antithetical to the purpose of a university, but is fascistic by relinquishing power to a few to decide what can be said, what speech is allowed, and what must be suppressed. It is what former Yale University president Bartlett Giamatti characterized as the “tyranny of group self-righteousness.”

In fact, at least three professors at other universities have already been punished for expressing views misaligned with Black Lives Matter and the ubiquitous narrative of “systemic racism” in policing.

Shortly after the murder of George Floyd, for instance, Professor Gordon Klein of UCLA received an e-mail from a student, which requested, on behalf of a number of black students, a “no-harm” final exam that could only benefit students’ grades and more lenient deadlines for final assignments. UCLA’s own regulations prohibit a professor from changing exam schedules, so Klein declined the request, adding some sarcastic responses to the email. For sending the email, Klein was placed on involuntary administrative leave and students called on the University to fire him, even though he had not violated any academic guidelines and the language of his response, while possibly off-color, was certainly protected academic free speech.

University of Chicago economics professor Harald Uhlig similarly found himself embroiled in controversy when he reasonably suggested on his Twitter feed that Black Lives Matter “torpedoed itself with its full-fledged support of #defundthepolice.” Uhlig is also editor of the Journal of Political Economy, and after he was accused of “trivializing the Black Lives Matter movement” with his tweet, fellow academics also attempted to strip him of his editorship, contending that Uhlig’s comments “hurt and marginalize people of color and their allies in the economics profession.” Uhlig was indeed suspended from his role, but was then reinstated after the university’s investigation found insufficient evidence of misconduct on Uhlig’s part.

Cornell’s William Jacobson was the target of attacks from campus activists after he posted criticism of Black Lives Matter’s mission and behavior on his blog, Legal Insurrection. “Concern for black lives, and all lives, is important,” Jacobson wrote. “But that is not the agenda of the Black Lives Matter movement, they seek to tear down our society to achieve their Marxist goals, and it takes a huge deception to get people to go along.” At a time when whites were getting on their knees and apologetically kissing the feet of black people, this commentary did not sit well with the Cornell community, including the University’s President, and particularly the Cornell Black Law Students Association (BLSA), which accused Jacobson of choosing “to weaponize these tragic losses (of black lives at the hands of police) at the expense of students of color.”

What is the lesson in each of these three cases, and why should this be a cautionary tale for the Princeton faculty? None of the professors expressed views that were actually bigoted, racist, or biased. In fact, their opinions about Black Lives Matter and the organization’s tactics and ideology were demonstrably true, regardless of if some students who read these views found them to be so-called “hate speech” that refused to “acknowledge the tangible harm caused by structural racism and oppression,” as the Cornell BLSA put it.

There is another, even more critical aspect of the ideology of the professoriate that would be an argument against making them responsible for finding and punishing instances of racism: while faculty and administrators have long expressed a fervent desire to create ideological diversity in academia, research studies have indicated that, in reality, nothing even close to this aspiration has been realized. In fact, in one of these investigations conducted by Daniel B. Klein and Charlotta Stern, the authors identify the existence of what they identified as highly-biased campuses where Democrats (liberals) outnumber Republicans (conservatives) at alarming rates of disparity, with “results [that] support the view that the social science and humanities faculty are pretty much a one-party system.” The study found that the ratios between Democrats and Republicans in the different academic departments ranged from a low of 3-to-1 in Economics to a shocking 30.2-to-1 imbalance of Democrats to Republicans among anthropology faculty. Another study, written by Mitchell Langbert and Sean Stevens and published by the National Association of Scholars, found that faculty political contributions at over one hundred elite colleges favor Democrats to Republicans 95:1.

So it is likely that professors who are openly contemptuous of conservative views, and who have decided in advance that these views are bigoted and intellectually defective, will never be motivated to even listen to opposing voices, let alone allow faculty with these views to express them to campus. This is precisely why the notion of having a committee of professors decide who is, and who is not, a racist is a critically flawed idea.

“Without sacrificing its central purpose,” suggested Yale’s still-relevant 1974 Woodward Report on freedom of expression, “[the university] cannot make its primary and dominant value the fostering of friendship, solidarity, harmony, civility, or mutual respect. To be sure, these are important values . . . [for a university, but not] its central purpose. We value freedom of expression precisely because it provides a forum for the new, the provocative, the disturbing, and the unorthodox.”

Princeton faculty should not be afraid of that freedom.

——

If you found this blog post of interest, you might want to explore these Thinker Education courses:

For this third party post in its full context, please go to:

Faculty Demand a Racism Star Chamber at Princeton

© 2020. Minding the Campus.