By Hal Boyd and Alan J. Hawkins | (Source)

In her recent New York Times article, “The Poly-Parent Households Are Coming,” Professor Debora L. Spar of Harvard Business School seems eager to welcome what she paints as the inevitable arrival of poly-parenting—babies biotechnologically conceived by any number of parent donors of every combination of biological sex.

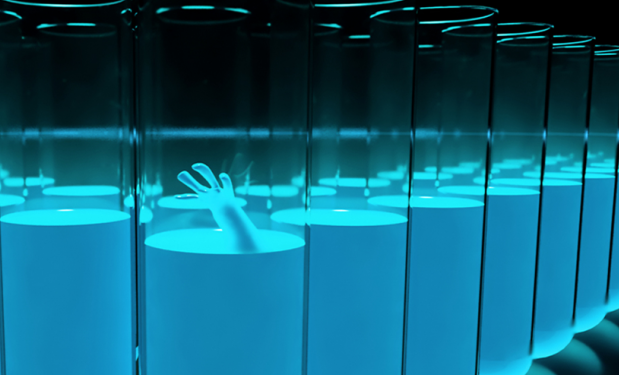

All this and more is facilitated by coming breakthroughs in in vitro gametogenesis, or IVG, technologies.

Cue the Jurassic Park theme music.

In this movie, however, the subjects aren’t computer-generated images but actual human beings. And there’s nothing fictional about it. Certainly, the advancements associated with in vitro gametogenesis—for example, gene-editing technologies—offer hope to aspiring parents who cannot conceive, and present exciting possibilities to provide a better life for children by eradicating certain diseases or genetic disorders.

But, the prospect of permitting lightly regulated baby-to-order services raises a number of thorny ethical questions.

We’re told, for example, that the coming IVG revolution aims in part “to dismantle completely the reproductive structure of heterosexuality. . . . Once we no longer need the traditional family structure to create children, our need for that traditional family is likely to fade as well.” Professor Spar sees a future in which not only same-sex couples will create their own babies but also single men, or even a group of platonic “housemates.” It’s worth noting that such an amorphous group today would not be able to adopt a child jointly, even if IVG technologies may soon help them make one.

Although Professor Spar concedes that IVG probably will not fully replace traditional sexual reproduction, she’s nonetheless bullish that this brave new world (reference, intended) will “undo or at least revise our centuries’ old conviction that procreative unions—like Noah’s animal—come only in pairs.” She envisions a “motlier crew” of parental “threesomes and foursomes” from across the “spectrum of gender identity.”

If all this seems like sexual liberalism’s own version of a Mary Shelley novel, Professor Spar is quick to assure readers that the origins of this “revolution” are “deeply conservative.” They’re inspired by the fundamental human yearning “to extend or re-create life’s most basic process of production.” This sounds conservative enough. But in Spar’s telling, the trajectory of this yearning is conservative in a way she seems less eager to highlight—her sketch of IVG is unapologetically capitalistic. It’s big on the upsides of this emerging technology’s ability to meet untapped market demands but less interested in its unknown effects on children’s health and well-being, not to mention its potentially adverse effects on societal norms.

Concern about the health risks of IVG reflect what scientists now know about in vitro fertilization, or IVF. Much of the early handwringing regarding in vitro fertilization has proved hyperbolic—some called it “the biggest threat since the atom bomb.” And yet, scientists today have become quite cautionary about many of the very real risks associated with IVF. Certainly, most children conceived through assisted reproductive technology turn out normal; but there’s increasing evidence that these technologies are linked to higher birth defects and other disorders. Studies show an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and even infant mortality.

This should make any scholar cautious about rushing into an unregulated world of IVG technologies. IVG after all is far more complex than IVF. Apart from the direct health risks that might attend emerging IVG technologies, it’s worth considering the potential effects on social well-being.

For starters, it seems the emerging IVG trend would swim upstream against important ethical concerns about accelerating social inequities. IVG services, like IVF, cost money. Lots of money. The IVF industry is already valued at nearly $20 billion with plenty of profits for cheerleading investors. Supporters see a world where paying customers can dial up the designer baby of their dreams—with the right eye color and IQ—potentially further exacerbating the gap between rich and poor.

And it’s not just traditional couples that can produce a child. But, if a group of three or four can purchase a designer baby, what about a group of 7 or 8? Could, say, a fraternity pay for their own baby mascot for the right price?

Such a vision is capitalism unchecked by common sense, let alone human conscience and the rights of innocent, unborn children. Thankfully, however, American society has in the past rightly rejected the idea that human life can be so easily, or recklessly, bought and sold.

Perhaps this is why some advocates—including Professor Spar—have chosen a different sales pitch: the dismantling of heterosexual norms.

It’s increasingly a political dogma that when it comes to people’s bedrooms (or, in this case, lab rooms) policymakers and jurists must stay out. Citizens should be free to form any imaginable familial arrangement without regard to how it may affect children or broader society. While such an ideology may maximize adult autonomy, it fails to properly take into consideration the true autonomy of children, our most vulnerable population.

Don’t get us wrong, we believe humans have fundamental freedoms and markets play an important role. But common-sense regulations deserve a hearing when formidable technologies emerge with the power to significantly modulate human reproduction process, and, by extension, human life. At a minimum, such technologies should receive far more scrutiny and skepticism than Professor Spar and other advocates seem willing to offer.

Call us unenlightened. But we question the necessity of so zealously supporting a biological libertarianism that will allocate substantial healthcare resources and scientific attention to a new, unproven technology driven by a desire to help a few elites break through the “oppressive” bonds of traditional family life, when so many disadvantaged children currently face challenges that deserve greater attention and resources.

In addition to the unchecked capitalistic undertones of Spar’s advocacy, there are other reasons to be concerned about exuberant advocacy for dethroning the stable, two-parent, heterosexual family as a fundamental institution that shapes human behavior in useful ways. Even with its warts, the traditional two-parent family continues on average to outperform other family forms that curious social scientists stack up against it. Looking at a wide array of measures of children’s wellbeing over decades of empirical inquiry, hundreds and hundreds of studies have found that children born to two-parent, married families consistently score higher, on average, than children of other households.

And it’s not just the children; the adults, on average, are happier, better adjusted, more engaged citizens—better off on just about any metric of adult wellbeing that one can measure. Of course, all this is not to say that children who experience other family forms are doomed, and individual outcomes vary widely. Certainly, children reared in two-parent heterosexual families have no guarantees, and many face significant domestic challenges. Life is hard and complex for many children born into even seemingly ideal circumstances. But from a societal perspective, the odds remain with the traditional family structure.

Not surprisingly, then, even today, the vast majority of Americans continue to aspire to a stable, two-parent family. Why then would Professor Spar or anyone else be so eager to dramatically change an institution that, from a scientific perspective, has proven itself to be the best environment, on average, for raising the next generation in socially responsible ways?

Although IVG is pitched as an inevitability, there’s nothing inevitable about it. The flipside of proposing a world where any collection of adults can choose a designer baby is an acknowledgement of the reality that humans can in fact choose a world of stable family structures. Citizens can choose to prudently embrace scientific advancement. We can tread cautiously on the production of human life—investigating the risks and benefits of IVG, guarding against excesses that will most certainly have undesirable impacts on human well-beings, while advancing proven benefits.

So, it’s back to Jurassic Park.

Sure, the plot is different. But we’d sure do well to consider the cautions of the character Dr. Ian Malcolm (played by Jeff Goldblum) who muses from behind his thick-rimmed glasses: “the lack of humility before nature that’s being displayed here staggers me.”

——

If you found this blog post of interest, you might want to explore these Thinker Education courses:

- Are Human Beings Just Animals?

- Have We Found Some Missing Links?

- Is Faith in God Really Compatible with Science?

For this third party post in its full context, please go to:

Poly-Parenting: Is This The Brave New World We Want?

© 2020. The American Conservative.