By Annie Holmquist | (Source)

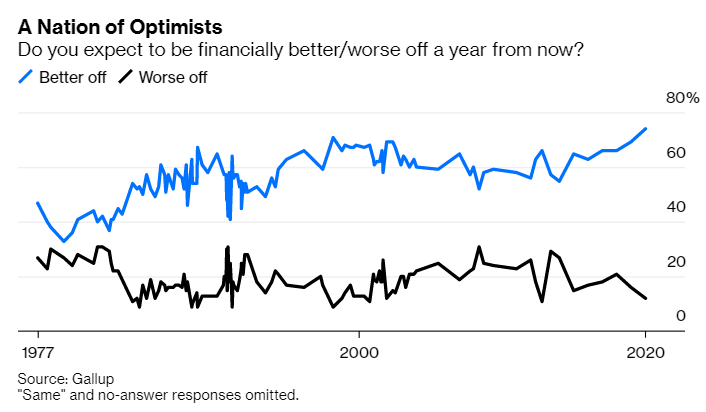

Just a few weeks ago I was surprised to see a headline indicating American confidence had increased over the past few years. The following chart from a January Gallup poll gives a glimpse into that confidence:

How quickly things change. As a friend recently told me, when everything looks good and optimism is up, that’s a sure sign everything is about to tank. Recently, all the headlines showcase stories of gloom and doom. Coronavirus. Falling stocks. Businesses struggling. Tumultuous primaries.

In this uncertainty, I stumbled on an intriguing quote in Whittaker Chambers’ Witness. Although written in the mid-20th century, it seems oddly fitting for our time. He notes:

[A]s 20th-century civilization reaches a climax, its own paradoxes grow catastrophic. The incomparable technological achievement is more and more dedicated to the task of destruction. Man’s marvelous conquest of space has made total war a household experience, and, over vast reaches of the world, the commonest of childhood memories.

Chambers’ next words, taken line by line, conjure images reminiscent of recent headlines:

“The more abundance increases, the more resentment becomes the characteristic new look on 20th-century faces.”

Americans – even those at the bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum – are better off than the rich of other nations. Yet we still experience anger and resentment, a fact underscored by the 80-plus percent of Americans believe their countrymen are angrier than a generation ago.

“The faster science gains on disease (which, ultimately, seems always to elude it), the more the human race dies at the hands of living men.”

We live in a time when vaccines and medications are commonplace. Scientific research into various health issues is always in full swing. Yet then a novel coronavirus hits, catching medical research off guard and raising fears in first world hearts, and it becomes clear that trust in modern medicine isn’t as sure as we thought.

“Men have never been so educated, but wisdom, even as an idea, has conspicuously vanished from the world.”

Millennials are the most educated generation in recent history, yet IQ scores in developed countries suggest that “people are getting dumber.” We send students through years of schooling, yet when it comes to using plain old common sense to navigate the adult world, our students seem to be lacking.

What caused these things to come to pass? Chambers offers a theory:

Under the bland influence of the idea of progress, man, supposing himself more and more to be the measure of all things, has achieved a singularly easy conscience and an almost hermetically smug optimism. The idea that man is sinful and needs redemption has been subtly changed into the idea that man is by nature good, and hence capable of indefinite perfectibility. This perfectibility is being achieved through technology, science, politics, social reform, education. Man is essentially, good, says 20th-century liberalism, because he is rational, and his rationality is (if the speaker happens to be a liberal Protestant) divine, or (if he happens to be religiously unattached) at least benign. Thus the reason-defying paradoxes of Christian faith are happily by-passed.

In essence, Chambers believes we have forgotten God and pursued perfection on our own, an assessment that seems to be confirmed in the growing number of religious “nones” in today’s society. Yet, as Chambers’ other observations testify, going it on our own is not producing very satisfying results.

With this in mind, would we be wise to acknowledge our human frailty and reexamine the relation we have to God, particularly in these times of uncertainty?

——

If you found this blog post of interest, you might want to explore these Thinker Education courses:

For this third party post in its full context, please go to:

Why Perfection Continues to Evade Society

© 2020. Intellectual Takeout.