By Deanna Briody | (Source)

“How can I find you on Facebook?”

“I don’t have one.”

Shock. Incomprehension. Even more than usual. Marwa’s lively brown eyes were clouded with concern. When she spoke, her voice was hushed, almost strained: “Why not?”

How in half a dozen years have I not come up with a good short answer for that question? A moment passed and I looked around, as if an explanation might appear somewhere amidst the tea cups.

No such luck. I shrugged. “I have no need for it.”

This was three years ago. Marwa and I sat in a café in Al-Azhar Park in the middle of Cairo, she in her beautiful, deep red burqa, me in my frumpy long skirt and a sheen of sweat. It was my first time in Egypt, and over the previous two weeks Marwa and I had become fast friends. Although I was a Christian, I was also a foreigner. My transience made me safe. We had talked about God and suffering and prayer and men and all number of taboo topics over the course of our time together. But my lack of social media troubled her to an extent that troubled me.

I was used to people being surprised over my choices surrounding technology. I was in my mid-twenties and had no presence on social media. I could navigate my laptop and phone adequately, but when it came to the minute up-to-datedness which a constantly reloading newsfeed gives you, I was a stranger in a strange land.

In Marwa’s eyes, though, it seemed I was willingly disconnecting myself from the very staff of life. When I voiced my confusion to an Egyptian missionary friend, she told me that in certain circles of the Islamic world, women had found in Facebook a sort of harbor of connectedness. Social media had become a place where they could participate in the outside world, in ways that were otherwise unavailable to them.

At the time, of course, there wasn’t a pandemic sweeping the globe, devastating nations, neighborhoods, and families, forcing women and men of every tribe and tongue to practice isolation and social distance. Marwa was not talking about her life during a pandemic. She was talking about her life.

It hit me like a brick. I recalled what I had seen and heard during my time in Egypt concerning the status and circumstances of women. I remembered a girl still in her teens describing in broken English her fear of getting married. “Your life no longer your life,” she said. “You there to make babies.” I thought of Marwa’s sharp, encompassing appraisal of her own male-dominant subculture: “There’s no freedom here for me, for women. You can’t work the jobs you want, have the friends you want. You’re trapped and kept away and seen as the charge and property of men.”

Social media wasn’t an amusement to Marwa: it was a lifeline. It was an avenue of connection in the midst of isolation, and through it, Marwa and others like her had formed relationships with each other – here were people they could write to, empathize with, console, and encourage. Not only this, but they also found a wider network of women and men, within the Muslim world and outside it, who saw them as people of equal worth and dignity and advocated on their behalf.

I thought back to my exchange with Marwa over Facebook. “I have no need for it,” I had told her, and my answer stood, but for the first time I saw the privilege it stood upon.

My life and technology’s role in it have looked very different from Marwa’s. I’ve almost always been free to go where I’ve wanted to go and be with the people I’ve wanted to be with.

All the same, by the time I was in high school, I was using AOL instant messenger to communicate with friends late into the night. I was the last of my peers to get a cell phone, but when I did get one, I liked texting just as much as they did. When I left for college, I took with me a Facebook profile of which I was, privately, quite proud.

Things have changed for me since then. I’ve long since disabled my Facebook account, grown a reputation among my friends as an infamously indifferent texter, and refused to get a blog or a Twitter, though I can no longer deny they would be helpful in service of my aspirations to be a writer.

I had no dramatic conversion. It’s not as if there was a single moment in which I realized that Facebook was causing me undue amounts of misery and loneliness, or that my iPhone was ruining my life. Conviction grew slowly over time, like hunger. In contemplating what constitutes a good life, I came to believe that the social technologies of our day don’t, generally speaking, bring us towards it.

Central to my growing understanding of the good life was what various writers have called Membership. Wendell Berry writes of Membership as a rootedness in place, a belonging in community, a way out of “lonely suffering” into wholeness. C. S. Lewis and G. K. Chesterton envision something similar: Lewis writes of a mystical Body in which one’s unique identity isn’t lost but is actually brought to its fullest realization in self-forgetful self-giving; Chesterton writes of a commitment to a tangible place and its people, a bound-ness to an imperfect world and its imperfect inhabitants, following after the God who has bound himself to the same.

I have experienced this Membership. I can’t say it’s been constant. It’s suffered many interruptions and a few agonizing breaches. Almost always it has manifested itself only partway, or fleetingly. Yet it has existed, and I have known it: in classrooms and at block parties; in living rooms and gardens; in the chapel, at the airport, around the dinner table; as hands grip hands to pray; as sweat joins sweat in work; as eyes hold eyes, and voices call beloved ones by name.

Rather than allow people fuller entrance into these contexts, more often than not social media platforms seemed to take people out of them. They didn’t enhance the cultivation of Membership, and sometimes it seemed they didn’t even allow for it.

Of course, it’s been weeks, even months, since many of us entered a church, or sat around a table with friends, or gathered to share and lighten our labor. The novel coronavirus has, for a time, stripped us of these social privileges. Confined to our own homes with severely limited company – and that company often strained and anxious – we taste the hunger that is for some daily bread.

In the years before the pandemic, my choices around technology reflected my privilege, but it was a privilege to which I was entirely blind. Since the good life was available to me, I assumed it was available to everyone.

Meeting Marwa made me think differently, and Covid-19 has brought her close. Like everyone else in this strange season, I find myself reliant on social technologies in a way I have never been before. Working as a tutor and adjunct from home, I’ve been meeting with my students online, and every week I feel deep in my gut the relief it is to see and hear them, even through a computer. Visiting an older friend who lives alone via FaceTime for an evening is a mercy for us both. Eating dinner on one side of the screen while my parents, hunkered down in their house in New York, sip wine and laugh with me on the other, is so kind a gift it makes my throat tight with gratitude.

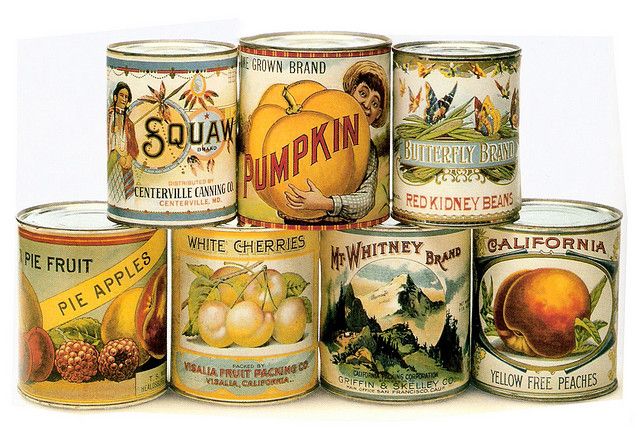

Marwa was the first to show me that social media could, in certain contexts, be a sort of divine provision: manna in the wilderness, or perhaps a more appropriate metaphor, tinned fruit. Tinned fruit travels safely and keeps, even through a pandemic, and our hungry souls are grateful for it. But if the past weeks have shown us anything, it is that preserves and compote are not nearly as satisfying, nor as salutary, as a freshly picked anything. “Fruit has to be tinned if it is to be transported,” C. S. Lewis once wrote, “and has to lose thereby some of its good qualities. But one meets people who have actually learned to prefer the tinned fruit to the fresh.”

No doubt Lewis was right. In these days of pandemic, however – when even the most privileged among us have been stripped of the luxury to choose the fresh when we want it – we can taste the difference between the two. We are being fed, even sustained by our digital connections, but we hunger for the restoration of incarnate communion. We are beginning to see that “ordinary life” is, for many of us, a veritable orchard.

At some point in the coming months, the pandemic will end. Social distancing will relax. Many of us will again have the privilege to go where we want to go and be with the people we want to be with; we will enjoy the freedom to commune, rather than merely connect. On that day, we will feast on what we did not plant.

Though not all of us. Many people will continue eating tinned fruit almost exclusively. Some, like Marwa, will eat it by necessity. Countless circumstances – cultural conditions, illness, disability, imprisonment, age, even geography – make social distance a norm, in peacetime and pandemic alike. This is something we must acknowledge and grieve. It will be a welcome symptom indeed if the coronavirus moves us with fresh zeal and compassion toward the sick, the outcast, and the lonely.

But some of us will continue eating tinned fruit because, as Lewis prophesied, we have learned to prefer it to the fresh. This is cause for caution and wisdom. When the time comes, we will all have choices to make. For those among us who will on that day walk with bleary, blinking eyes back into the sunlit privilege of life in an orchard, may we then have the eyes to see it for what it is: an undeserved gift, pure grace.

——

If you found this blog post of interest, you might want to explore these Thinker Education courses:

- Do You Have a Life Stewardship Strategy?

- How Much Land Does a Man Need?

- Should We Eat Compassionately?

For this third party post in its full context, please go to:

Tinned Fruit in Times of Famine

© 2020. The Plough.