By Megan Briggs | (Source)

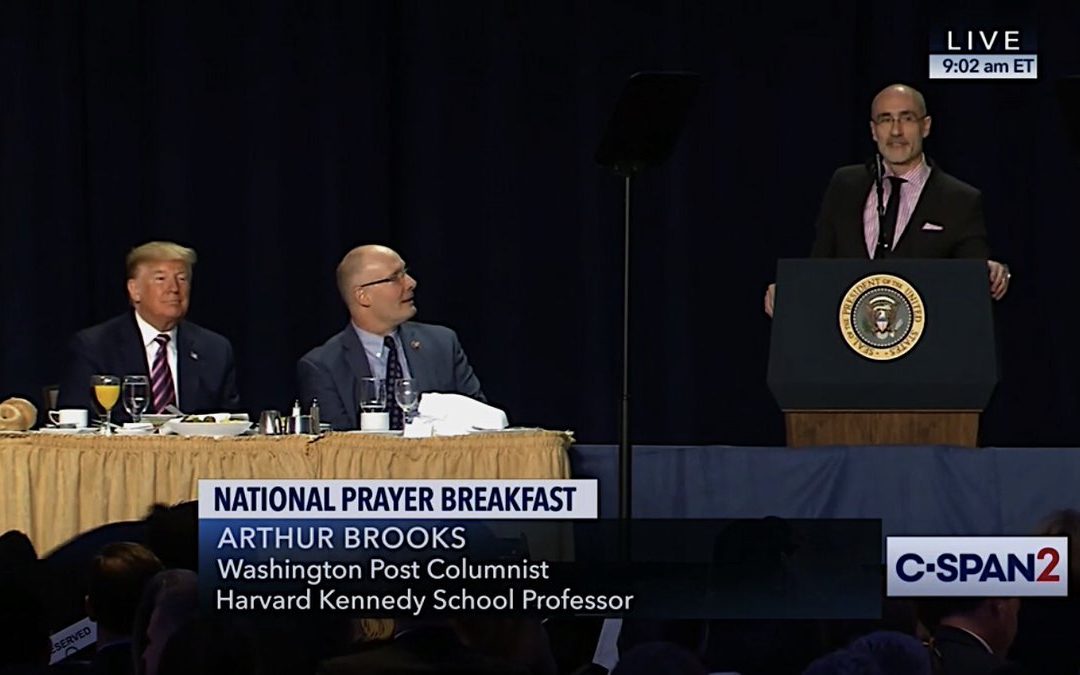

Arthur Brooks, a Harvard professor and former president of the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute (AEI), delivered a timely speech at this year’s National Prayer Breakfast in Washington, D.C. on February 6, 2020. Brooks, who introduced himself “first and foremost a follower of Jesus,” focused on the words of Jesus which encourages compassion toward one’s enemies–political or otherwise. Brooks’ remarks, while seemingly perfect for a bipartisan event such as the National Prayer Breakfast, were overshadowed by President Trump’s remarks immediately following.

Brooks said he was going to talk about “the biggest crisis facing our nation and many other nations today” and proceeded to address the “crisis of contempt and polarization” that is “tearing our society apart.”

However, Brooks kept his speech positive, saying he believes that within the crisis “resides the greatest opportunity we have ever had as people of faith to lift our nations up and bring our people together.”

Calling Jesus “history’s greatest social entrepreneur,” Brooks spoke on Matthew 5:44, where Jesus told us to love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us. Brooks said This thinking changed the world 2,000 years ago, and it’s as “subversive and counter-intuitive today as it was then.”

The professor and author then went on to describe how this advice might play out practically, especially in the divisive world of politics and partisan leadership. Brooks suggested making the issue personal. He gave an example from his own life. Brooks is from Seattle, a city he acknowledges is very liberal. His parents were good, moral people who led him into a personal faith in Jesus Christ; they were also liberal like most other people living in Seattle. Brooks says this experience helps him refrain from vilifying liberals as evil and stupid. He also emphasized that we can really only persuade other people to join our thinking with love, not argument.

“How many of you love somebody with whom you disagree politically?” Brooks asked the group of politicians. Raising his own hand, Brooks indicated they all should raise their hands if they do love such a person. At this point, President Trump, who was sitting to Brooks’ right side and in the camera shot, didn’t raise his. Brooks then said that moral courage isn’t necessarily standing up to your enemies or the people who disagree with you. Rather, it is standing up to the people with whom you agree on behalf of those with whom you disagree. “Can you do it? Are you up for it?” he asked the room.

One of the main points Brooks made is that anger is not the problem–contempt is. Quoting 19th-century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, Brooks defined contempt as “the unsullied conviction of the worthlessness of another.” When we treat each other this way, Brooks argued, this is what makes our disagreements “so bitter” and causes us to feel cooperation is “nearly impossible.”

Some say we need more civility and tolerance. “Nonsense,” Brooks said. “Jesus in the Gospel of Matthew didn’t say tolerate your enemies, he said love your enemies.” But how are we to do this in our day and age?

Brooks Gave three pieces of “homework” to those in attendance:

- Ask God to give you the strength to do this hard thing of loving your enemies. Brooks said this would require going against your own human nature.

- Make a commitment to someone else to reject contempt. Brooks said rejecting contempt doesn’t look like setting aside disagreement. Rather, disagreement is good–in fact, “what makes America great is the competition of ideas, that’s part of democracy.” But Brooks called on the politicians to disagree without contempt. Ask someone to hold you accountable, he advised. Public leaders, for instance, could make this commitment publicly.

- Go out looking for contempt and turn it on its head. This is how we will change the country, Brooks explains. Think like a missionary, Brooks admonished the group. Go out looking for opportunities to show love to people who disagree with you and who show you contempt. Additionally, if you can’t find contempt, you need a wider circle of friends, as “you’re in an echo chamber,” Brooks said.

——

If you found this blog post of interest, you might want to explore these Thinker Education courses:

For this third party post in its full context, please go to:

© 2020. Church Leaders.