By Anthony Esolen | (Source)

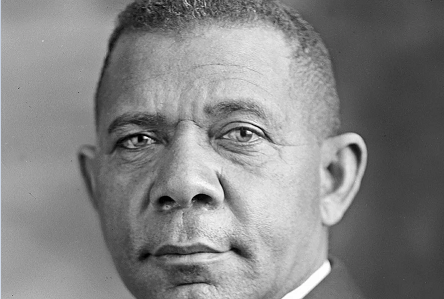

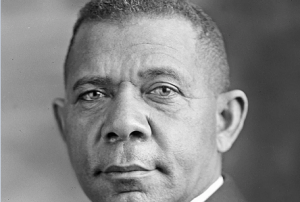

My experience,” wrote Booker T. Washington in Up From Slavery, “is that there is something in human nature which always makes an individual recognize and reward merit, no matter under what color of skin merit is found. I have found, too, that it is the visible, the tangible, that goes a long ways in softening prejudices. The actual sight of a first-class house that a Negro has built is ten times more potent than pages of discussion about a house that he ought to build, or perhaps could build.”

Washington had dedicated his life to raising up young men and women of his race in the agricultural and industrial arts—in producing “the visible, the tangible.” It was the inspiration behind the work of his friend and mentor, General Samuel C. Armstrong, at the Hampton School, now Hampton University, where Washington himself acquired his own education. With Armstrong’s encouragement, Washington went to the “Black Belt” of Alabama, secured some fallow land and a disused and dilapidated church in the countryside, and proceeded to build up the Tuskegee Institute.

The boy who slept under a wooden sidewalk in Richmond as he worked in the day and saved up nickels to make his way to Hampton became the man who, as he said, had to make “bricks without straw.” There were no beds for the students to sleep on. There were no dishes for their suppers. There were no chairs, so the students would nail three flat boards together to sit on. They had, he said, to “[make] their beds before they could lie on them.”

Washington took a rightful pride in what he, his teachers, and his students had done with their own hands. “I am glad that we endured all those discomforts and inconveniences,” he wrote. “I am glad that our students had to dig out the place for their kitchen and dining room. I am glad that our first boarding-place was in that dismal, ill-lighted, and damp basement.” Years later, if one of the students was tempted to take his knife and etch his name into a wall, an older fellow would take him aside and tell him not to do it, because he had been one of the young men who put up that wall.

That was the case with almost all the buildings at Tuskegee. The students built them. They even made the materials with which to build them. It took four attempts, but at last, they fashioned a kiln for firing bricks, which according to Washington produced 1.2 million bricks in a single year. The bricks were of such high quality that their white neighbors began to prize them too.

That was Washington’s aim: the respect you earn by the quality of work you do, work in what is useful and good. That was how a man could entwine himself into the life of a community.

“I spoke of an instance,” said Washington of a five-minute speech he traveled 2,000 to give, “where one of our graduates had produced two hundred and sixty-six bushels of sweet potatoes from an acre of ground, in a community where the average production had been only forty-nine bushels to the acre. He had been able to do this by reason of his knowledge of the chemistry of the soil and by his knowledge of improved methods of agriculture.”

“The white farmers,” he pointed out, “honored and respected him because he, by his skill and knowledge, had added something to the wealth and the comfort of the community in which he lived.”

Washington could not have achieved what he did without a strict code of morality, made manifest in his almost obsessive demand for cleanliness, strict scheduling, and a precise account of everything that the school did and consumed and produced. Here is an outline of their workday:

5 A.M., rising bell; 5:50 A.M., warning breakfast bell; 6 A.M., breakfast bell; 6:20 A.M., breakfast over; 6:20 to 6:50 A.M., rooms are cleaned; 6:50, work bell; 7:30, morning study hour; 8:20, morning school bell; 8:25, inspection of young men’s toilet in ranks; 8:40, devotional exercises in chapel; 8:55, “five minutes with the daily news;” 9 A.M., class work begins; 12, class work closes; 12:15 P.M., dinner; 1 P.M., work bell; 1:30 P.M., class work begins; 3:30 P.M., class work ends; 5:30 P.M., bell to “knock off” work; 6 P.M., supper; 7:10 P.M., evening prayers; 7:30 P.M., evening study hours; 8:45 P.M., evening study hour closes; 9:20 P.M., warning retiring bell; 9:30 P.M., retiring bell.

College life in general in those days was spartan, not epicurean, so that youths were more likely to leave strengthened and not riddled with physical or moral diseases. Yet I doubt that Harvard boys and Radcliffe girls had anything like this all-encompassing commitment to work.

Washington became the spokesman for blacks throughout the nation, meeting encouragement wherever he went, which he never failed to note and to appreciate, understanding that generous appeals to men’s better nature could open hearts, where blame, even when justly directed, would but cause embitterment.

He gave so much of himself to Tuskegee and to his fellow blacks, traveling constantly, raising money, speaking to groups of all sorts, that he drove himself to an early death of high blood pressure, at age 59. I do not know whether any single human being worked harder for racial reconciliation than did Booker T. Washington.

We might ask what lessons Washington’s career has for us in America now, in bringing about racial harmony. The problem, as I read Up From Slavery, is that we no longer have the human beings to put the lessons into action.

It wrings the heart to hear of such men as Robert Gould Shaw, who gave his life leading the first Negro regiment in the Union Army; Washington was present at the festive unveiling of the Shaw Memorial and its mural sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, which was recently vandalized. It abashes me to hear of the kindliness and the simple humility of the presidents whom Washington met, Republicans Benjamin Harrison and William McKinley, and Democrat Grover Cleveland. It was a time when bishops were the moral leaders of their communities, instead of the foul-mouthed, ignorant actors and sleazy singers we follow today.

I do not mean that the customs of that time were all sweetness and light. Washington knew he was the first black man whom some white people ever addressed as “Mister.” He knew about (and trusted was a temporary stage in America’s development) social segregation, racial prejudice (which he said harmed the hater more than the hated), and crimes against his people, such as lynching.

But most of their customs produced men of impressive achievement and earnest care for what Russell Kirk would call “the permanent things.” People supposed, perhaps with too much confidence, that moral improvement in America was keeping pace with her material improvement. Now all of that seems like the rusted and sea-twisted iron of a ship, wrecked against the rocks and sunk into the seabed, unseen and forgotten.

We are now such people as neither the whites nor the blacks of Washington’s time would want their children to associate with.

What could Booker T. Washington do with us now? We scorn physical labor. We have few practical skills. We are slovenly, slack, and unmanly. We cannot have a serious truth-telling discussion about anything. Family life is riddled with holes. We have enslaved ourselves to our appetites. Some of those appetites are for what pleases us for a while at least, only to leave us dispirited and sullen. Others are appetites for vengeance, enmity, and destruction. We raise our children to expect that they should decide what they want and to go for it, rather than that they should tailor what they want to their duty, what they should do.

Washington believed that his work succeeded because it was in concord with immutable laws of human nature. But we now believe that there is no such thing as human nature; all is the production of politics. If we are wrong about that, and if every great civilization in human history has been correct, then we are worse off than people trying to make bricks without straw. We are trying to make bricks without clay.

——

If you found this blog post of interest, you might want to explore these Thinker Education courses:

- Do You Have a Life Stewardship Strategy?

- How Do People Overcome Adversity?

- Is Moral Education Truly Important?

For this third party post in its full context, please go to:

© 2020. American Greatness.