Timothy Dwight wrote in 1798: “Religion and liberty are the meat and drink of the body politic. Withdraw one of them and it dies…Without religion we may possibly retain the freedom of savages, but not the freedom of New England…If our religion were gone, our state of society would perish with it and nothing would be left worth defending.”

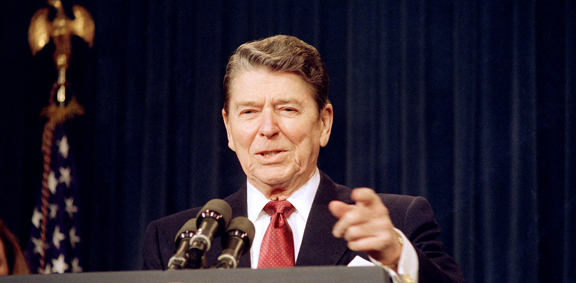

Tony Perkins shows that while reflecting consensus values in American society until late in the last century, social conservatism as a movement emerged in the early 20th century mostly in response to attacks on the Bible, and especially the teaching of evolution in public schools. Fading out of public view for a while, it came back to prominence as a movement in the 1980s through the Moral Majority. President Ronald Reagan championed the values of social conservatives and won in landslide elections in 1980 and again in 1984.

In every election since 1976, social conservatives or “value voters” have been a prominent part of the voting bloc. Currently a strong one-fourth of all voters consider themselves to be a “value voter” – and half of the GOP voters identify themselves as such. Many political tacticians believe that social conservatism today stands as a potential bridge for Republicans to the Hispanic and Asian voting populations, as both of these ethnic communities hold views of family and morality that would be considered more conservative than liberal.

Because of the relationship between religion, culture and politics, social conservatives believe that voting reflects one’s creed at a core level. While social conservatives agree on most economic matters with Libertarians, they believe in government upholding a strong moral standard, while Libertarians press for ethical individualism. While social conservatives believe in limited government, they also believe in separation between Church and the State. At the same time, that was never supposed to mean a separation of a reverence of God from society.

Most social conservatives take the long view with their voting and political leanings, choosing to consider how things will move through the generations rather than through an election cycle. And despite the regular “obituaries” written in the modern press about the social conservative movement, it looks to be a force in politics for decades to come. No matter one’s political perspective, it deserves careful consideration.

“Tradition,” as Chesterton observed, “is the democracy of the dead.” It is the consensus of those who have lived before us. Social conservatives have represented the standing tradition of social morality in America until very recently. As progressives continue to press their agenda in modern America, the movement will face the new challenge of convincing people that real progress “means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road.”

_17422494921.png )