By Natalie Scholl (Source) | AEI’s Values and Capitalism program just released a new book titled “Entrepreneurship for Human Flourishing.” In it, the authors, Chris Horst and Peter Greer, argue that entrepreneurial businesses, “which sustain productive development long after charitable giving dries up,” are the real engine of true human flourishing. Here, Horst and Greer answer a few questions about the book.

How does entrepreneurship connect to human flourishing, and can you provide a real-life example to illustrate?

Peter and I work at an intersection between two worlds: we help micro-entrepreneurs in the developing world start small businesses. We also interact with successful businesspeople in the US. Whether through corporations or microbusiness, entrepreneurs are transforming society.

I think of our friend Henry Kaestner. Henry is a risk taker. The entrepreneur from Durham, North Carolina founded a telecommunications company, Bandwidth, which now employs over 550 people and grossed more than $140 million annually. Passionate about business, he is now investing in emerging markets. “We believe small business are the lifeblood of every economy,” shared Kaestner. For example, he invests in CloudFactory, a company in Nepal’s capital Kathmandu. In a country with a 46% unemployment rate, the company hires software engineers to process and aggregate data, like a virtual assembly line.

Today CloudFactory is poised to become of the biggest employers in Nepal. People like Henry see the impact of business to elevate the level of living circumstances both here and abroad. They also see it as a way to draw people in to unleash their potential.

In your discussion of the importance of personal fulfillment, you say there’s a need to “recapture a restored vision of vocation.” What does that mean?

As “humanitarian professionals,” we have the privilege of attending and participating in many justice and poverty alleviation conferences. And I have yet to find a normal businessperson on the agenda at such conferences. That is truly disappointing.

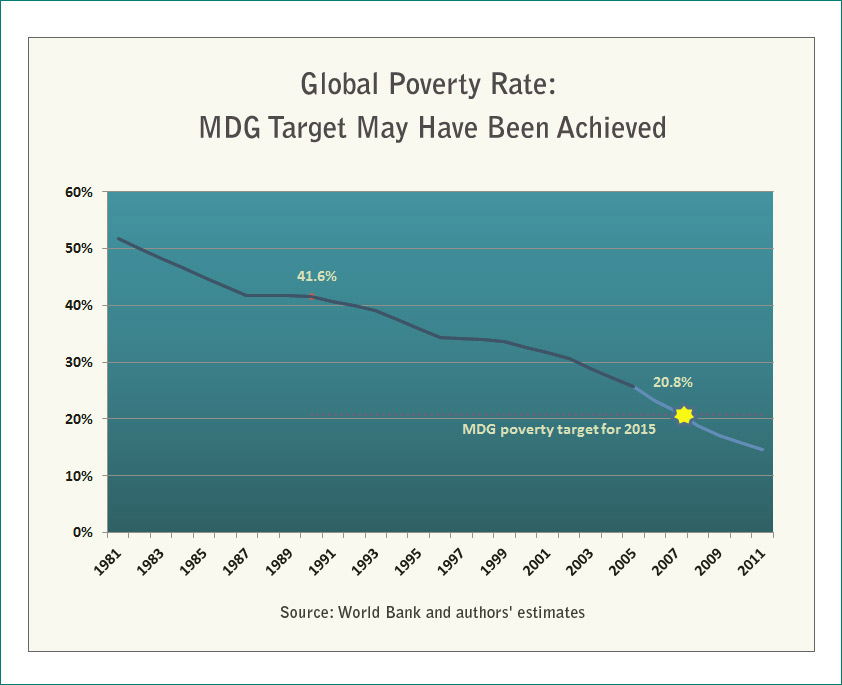

A job is the central weapon to the war on poverty. Yale University and the Brookings Institution recently released studies on the overwhelming decline in poverty in the last 20 years. According to their study, in 1981, 52% of the world’s population was unable to provide for their basic needs, like housing and food and was living below the “extreme poverty line.” By the end of 2011, just 30 years later, that percentage plummeted to about 15%. (See figure below).

That was due not to the World Bank or the United Nations, but rather to the “rise of globalization and the spread of capitalism.” Because of the role of business in poverty alleviation, we hope that someday at a conference focusing on economics and development, the role of business would be celebrated.

This is a long way of prefacing a short answer to your question: no one industry or vocation has the market cornered on helping the vulnerable. For people and places to be healthy, we need a rich ecosystem of businesses and nonprofits working together toward the flourishing of people. Plumbers, accountants, technologists, and manufacturers all have roles to play. Yet, when thinking about poverty alleviation—as evidenced by the speaker rolls at justice and poverty conferences—we’re quick to celebrate the social workers, humanitarians and educators, inadvertently suggesting that only these jobs really make a difference in the world. This just isn’t true. It’s why we need to expand our perspective on work.

The book notes that “there’s a direct correlation between the ease of opening a small business and a region’s prosperity.” In high-income countries small businesses employ more than 60% of workers versus 30% in low-income countries. Why is that?

In many low-income countries, the barriers facing potential entrepreneurs are onerous. Since 2003, The World Bank has been publishing its “Ease of Doing Business Report,” which ranks every country based on the ease of registering a new business, levels of business taxation, reliability of the power grid, and degree of corruption, among other variables. Their analysis is compelling: “Enabling growth—and ensuring that all people, regardless of income level, can participate in its benefits—requires an environment where new entrants with drive and good ideas can get started in business and where good firms can invest and grow, thereby generating more jobs.”

To combat poverty, countries must open their borders to trade and make the business climate conducive and welcoming to entrepreneurs. In developing countries, specifically, businesses provide an estimated 90% of all jobs. Leaders who recognize these realities have aggressively positioned their policies accordingly. While the private sector provides the bulk of jobs in these countries, these jobs are concentrated at either end of the business spectrum. Massive companies and informal, grassroots businesses are strong, but there is a gaping hole in between. Countries like South Korea and Taiwan flourished economically over the last century—and Rwanda and Ghana are surging right now—because of their emphasis on improving the entrepreneurial climate in their countries.

What are the biggest challenges facing entrepreneurs today, and what can be done to boost entrepreneurship both in the US and abroad?

Gallup reported that Americans’ trust in big business declined from 45% in 1975 to 21% in 2013. Yet all the while, trust in small business remained remarkably high. Sixty-five percent placed confidence in the institution of small business.

We all love a good rags-to-riches entrepreneur story. From the barbershop owner to the bold inventor like Henry Ford, these stories are quintessential Americana. But do we love when these businesses become big? Or would we rather they simply stay small? Small businesses often feel more human. Big businesses seem faceless. Startups feel approachable. Corporations seem impenetrable. Young Americans are enthusiastic about entrepreneurship and there is a renewed passion for craftsmanship—some call it the “maker movement”—in this country. The challenge will be whether this growing startup fascination will renew the American sentiment about the role of business in society.

In his book, “The Coming Jobs War,” Jim Clifton, CEO of Gallup, looked at Gallup’s volumes of global research and came to this conclusion: the most significant global issue in our time—more pressing than even environmental degradation or terrorism—is job creation. “If countries fail at creating jobs,” says Clifton, “their societies will fall apart. Countries, and more specifically cities, will experience suffering, instability, chaos, and eventually revolution.” As a country, we need to continue to celebrate entrepreneurship, create the best environments for business in our cities, and promote exemplars, companies that model well the enduring purpose of enterprise.

Where does big business fit into this, if at all?

Big business can be seen as the enemy of human flourishing. Certainly cases exist where this is true. But we believe this is the exception. And we love hearing stories of individuals working in big business who are using their platform to do good.

Consider Elyse Bealer. A native of the Cherokee tribe, Elyse wanted to be an advocate on her people’s behalf. When she graduated college with a degree in chemical and bimolecular engineering she could have worked for a nonprofit to advocate for the Native American population, but she realized that she had the greatest platform to help her people with Merck, a Fortune 100 pharmaceutical conglomerate.

Today, Elyse has led Merck to create Project Sacred Dream—a business plan for a call center that employs 500 people in Cheyenne River Sioux reservation in South Dakota. Ninety percent of the population is unemployed. When Elyse helps her people, Merck also benefits. The Native American population is an emerging healthcare market, expected to increase 33% by 2050. When passionate and driven individuals like Bealer work hand in hand with corporations like Merck, good can be carried out on a large scale.

Final thoughts?

The March 2011 Time cover story highlights 10 provocative ideas that are “changing your life.” Its “idea seven” opened with the statement, “What if the good life isn’t really … all that good?” It went on to ask, “What if the very things so many of us strive for—a high-paying, powerful job; a beautiful house; a wardrobe of nice clothes in desirably small sizes; and a fancy education for our children to prep them for carrying on this way of life—turn out to be more trouble than they’re worth?”

Through research, the authors discovered that once you reach a threshold of wealth, the advantages diminish: “Research indicates that as you near the top, life stress increases so dramatically that its toxic effects essentially cancel out many positive aspects of succeeding.”

In essence, they discovered what King Solomon, one of the richest and most successful men in the world’s history, wrote about in his memoir, the Book of Ecclesiastes, “Whoever loves money never has money enough; whoever loves wealth is never satisfied with his income.” Essentially Solomon is saying “Money alone doesn’t buy happiness.” We were created for more. In many corners of the business community, the purpose of business has been lost. And the dream many of these folks are chasing will never fulfill the deeper needs of the human heart and of our communities. In this book, we champion the important role enterprise plays in society, but we would be wise to heed Solomon’s warning. Financial prosperity alone is an unsatisfying and incomplete aim.

If you found this blog post of interest, you might want to explore these Free Think University courses:

For this third party post in its full context, please go to:

Entrepreneurship for Human Flourishing: A Q&A with Chris Horst and Peter Greer

© 2014. The American Enterprise Institute. www.aei-ideas.org