By Jim Norton | Can we please stop embarrassing ourselves by pretending these apologies mean anything and admit they are simply a bloodless way to satisfy our bloodlust?

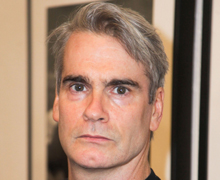

I am disgusted with Henry Rollins. How could he be so insensitive? What he said about Robin Williams was extraordinarily offensive and hurtful. Don’t get me wrong, I believe in free speech, but the things he said were way over the line. He definitely owed everyone an apology.

The predictable cycle of outrage and apology is Western Civilization’s newest craze. Since Robin Williams’ suicide, Todd Bridges has apologized for calling it “a very selfish act”; Shepard Smith has apologized for having the nerve to question whether it made Williams a coward; Rollins apologized for his opinions on suicide in general; Gene Simmons has gone back and apologized for things he said about depression and suicide in an interview that had nothing to do with Robin Williams whatsoever.

All four of these men made the critical error of giving opinions on suicide that didn’t fit a polite narrative. Which in 2014 means each of them must bow their heads and apologize—or suffer the witch-hunt consequences of having an unpopular opinion. Questioning or criticizing someone’s decision to commit suicide is not insensitive or unfeeling. It’s a part of the open and honest and difficult conversation we claim to want.

We cannot continue to delude ourselves into thinking we value such conversations when what we really value is publicly flogging anyone who contributes something to the conversation that we find disagreeable. Or—brace yourselves—offensive. For a country that claims to want an open dialogue, and to treasure free speech, we sure seem to enjoy mob justice against people who give an opinion contrary to the one we are comfortable hearing. Instead of physically beating someone to death, we feign shock, outrage and emotional anguish, until the person (or more likely the publicist) breaks down and begs our forgiveness.

Can we please stop embarrassing ourselves by pretending these apologies mean anything to anybody and own up to the fact they are simply a bloodless way to satisfy our bloodlust? Why exactly is it such a social crime to talk about the selfish nature of committing suicide? Why do people respond to such points by angrily stating how much pain the individual was in? Can’t both opinions be valid? Being in pain and behaving selfishly are not mutually exclusive.

I am not an expert in depression or suicide. What I know about suicidal feelings comes only from what I’ve experienced, not case studies or statistics. But I can tell you what it’s like to look over the edge of a cliff and convince yourself that jumping is the only option. In those moments, I saw only my own pain and was convinced that I would be doing nothing more than wiping a valueless person off the face of the earth.

Just because I was in pain doesn’t mean I wasn’t also thinking selfishly. That’s not to say that anyone who commits suicide is selfish, but it’s an observation one shouldn’t be crucified for making.

Which brings me back to apologies. Our cultural obsession with them isn’t about actually being offended, or simply needing to hear, “I’m sorry.” It’s not really about right or wrong. It’s about wanting to throw a rock in the dark and hear something break.

In the increasingly deafening and constantly morphing conversations on social media, it becomes more and more impossible for an individual and his or her opinions to stand out or to be heard. Going on Twitter or Facebook to gently voice dissatisfaction about something that someone said garners the same results as walking into a New Year’s Eve party and muttering to yourself in the corner. No one hears you or cares; it’s the ultimate form of social emasculation. It feels small and helpless.

But if you can get a few people at the party to scream with you at the same time, the rest of the people, who are enjoying themselves, will be forced to stop their revelry and take notice. And if, God forbid, you loudly announce you’ve been wounded, not only will everyone forget what they were saying and focus all of their attention on you; they will rally around you. They’ll listen to you. And most importantly, they’ll want to punish whoever hurt you.

No longer will you be the quiet person in the corner who has to live with the fact you heard something you didn’t like, you’ll be the one everyone is listening to and responding to and paying attention to.

Yet your offense at someone’s opinion should not be a precursor to further action. “I don’t like what you just said,” should end with a period, not a semicolon. When a celebrity offers a prescribed public apology, I feel nothing for them, and strangely embarrassed for the rest of us for requiring it. Even those of us who didn’t encourage the groveling are at best complicit because we watched the vultures circle instead of making some sort of effort to shoo them away.

We have become a country of voyeurs and rubberneckers who love nothing more than provoking a situation solely for the gratification of eliciting a response, then we convince ourselves we’re outraged so we can stand and watch the fire burn. A mouth full of broken teeth has been replaced with a tearful mea culpa in front of a bank of microphones.

The onslaught of fake outrage and insincere apologies is doing nothing to make our society a more compassionate, forgiving or understanding place. We are simply being trained to doubletalk and lie to avoid trouble. If we can’t think of a good lie or acceptable middle ground, we are taught to play it safe or say nothing at all.

And that makes me truly sorry. For all of us.

If you found this blog post of interest, you might want to explore these Free Think University courses:

For this third party post in its full context, please go to:

It’s Time for Celebrities to Apologize – For All Their Apologizing

© 2014. Time Magazine. www.time.com