While the Bashkirs were disputing, a man in a large fox-fur cap appeared on the scene. They all became silent and rose to their feet. The interpreter said, “This is our Chief himself.”

Pahom immediately fetched the best dressing-gown and five pounds of tea, and offered these to the Chief. The Chief accepted them, and seated himself in the place of honor. The Bashkirs at once began telling him something. The Chief listened for a while, then made a sign with his head for them to be silent, and addressing himself to Pahom, said in Russian:

“Well, let it be so. Choose whatever piece of land you like; we have plenty of it.”

“How can I take as much as I like?” thought Pahom. “I must get a deed to make it secure, or else they may say ‘It is yours,’ and afterwards may take it away again.”

“Thank you for your kind words,” he said aloud. “You have much land, and I only want a little. But I should like to be sure which bit is mine. Could it not be measured and made over to me? Life and death are in God’s hands. You good people give it to me, but your children might wish to take it away again.”

“You are quite right,” said the Chief. “We will make it over to you.”

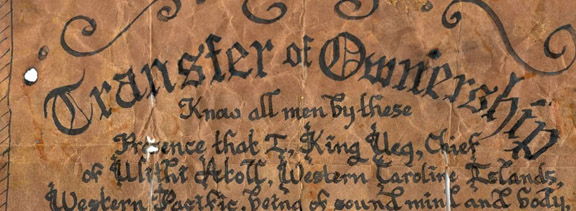

“I heard that a dealer had been here,” continued Pahom, “and that you gave him a little land, too, and signed title-deeds to that effect. I should like to have it done in the same way.”

The Chief understood.

“Yes,” replied he, “that can be done quite easily. We have a scribe, and we will go to town with you and have the deed properly sealed.”

“And what will be the price?” asked Pahom.

“Our price is always the same: one thousand rubles a day.”

Pahom did not understand.

“A day? What measure is that? How many acres would that be?”

“We do not know how to reckon it out,” said the Chief. “We sell it by the day. As much as you can go round on your feet in a day is yours, and the price is one thousand rubles a day.

Pahom was surprised.

“But in a day you can get round a large tract of land,” he said.

The Chief laughed.

“It will all be yours!” said he. “But there is one condition: If you don’t return on the same day to the spot whence you started, your money is lost.”

“But how am I to mark the way that I have gone?”

“Why, we shall go to any spot you like, and stay there. You must start from that spot and make your round, taking a spade with you. Wherever you think necessary, make a mark. At every turning, dig a hole and pile up the turf; then afterwards we will go round with a plough from hole to hole. You may make as large a circuit as you please, but before the sun sets you must return to the place you started from. All the land you cover will be yours.”

Pahom was delighted. It was decided to start early next morning. They talked a while, and after drinking some more kumiss and eating some more mutton, they had tea again, and then the night came on. They gave Pahom a feather-bed to sleep on, and the Bashkirs dispersed for the night, promising to assemble the next morning at daybreak and ride out before sunrise to the appointed spot.