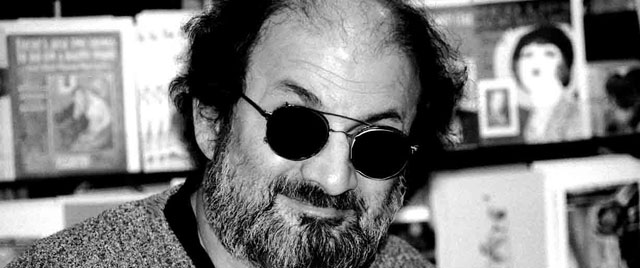

Having tasted of his work, you now can read about how his art changed his life in his own words. The following article is taken from The New Yorker and is authored by Salman.

THE DISAPPEARED

How the fatwa changed a writer’s life.

By Salman Rushdie | The New Yorker, September, 2012

Afterward, when the world was exploding around him, he felt annoyed with himself for having forgotten the name of the BBC reporter who told him that his old life was over and a new, darker existence was about to begin. She called him at home, on his private line, without explaining how she got the number. “How does it feel,” she asked him, “to know that you have just been sentenced to death by Ayatollah Khomeini?” It was a sunny Tuesday in London, but the question shut out the light. This is what he said, without really knowing what he was saying: “It doesn’t feel good.” This is what he thought: I’m a dead man. He wondered how many days he had left, and guessed that the answer was probably a single-digit number. He hung up the telephone and ran down the stairs from his workroom, at the top of the narrow Islington row house where he lived. The living-room windows had wooden shutters and, absurdly, he closed and barred them. Then he locked the front door.

It was Valentine’s Day, but he hadn’t been getting along with his wife, the American novelist Marianne Wiggins. Five days earlier, she had told him that she was unhappy in the marriage, that she “didn’t feel good around him anymore.” Although they had been married for only a year, he, too, already knew that it had been a mistake. Now she was staring at him as he moved nervously around the house, drawing curtains, checking window bolts, his body galvanized by the news, as if an electric current were passing through it, and he had to explain to her what was happening. She reacted well and began to discuss what they should do. She used the word “we.” That was courageous.

A car arrived at the house, sent by CBS Television. He had an appointment at the American network’s studios, in Bowater House, Knightsbridge, to appear live, by satellite link, on its morning show. “I should go,” he said. “It’s live television. I can’t just not show up.”

Later that morning, a memorial service for his friend Bruce Chatwin, who had died of AIDS, was to be held at the Greek Orthodox church on Moscow Road, in Bayswater. “What about the memorial?” his wife asked. He didn’t have an answer for her. He unlocked the front door, went outside, got into the car, and was driven away. Although he did not know it then—so the moment of leaving his home did not feel unusually freighted with meaning—he would not return to that house, at 41 St. Peter’s Street, which had been his home for half a decade, until three years later, by which time it would no longer be his.

At the CBS offices, he was the big story of the day. People in the newsroom and on various monitors were already using the word that would soon be hung around his neck like a millstone. “Fatwa.”

“I inform the proud Muslim people of the world that the author of the “Satanic Verses” book, which is against Islam, the Prophet and the Koran, and all those involved in its publication who were aware of its content, are sentenced to death. I ask all the Muslims to execute them wherever they find them.”

Somebody gave him a printout of the text as he was escorted to the studio for his interview. His old self wanted to argue with the word “sentenced.” This was not a sentence handed down by any court that he recognized, or that had any jurisdiction over him. But he also knew that his old self’s habits were of no use anymore. He was a new self now. He was the person in the eye of the storm, no longer the Salman his friends knew but the Rushdie who was the author of “Satanic Verses,” a title that had been subtly distorted by the omission of the initial “The.” “The Satanic Verses” was a novel. “Satanic Verses” were verses that were satanic, and he was their satanic author. How easy it was to erase a man’s past and to construct a new version of him, an overwhelming version, against which it seemed impossible to fight.

He looked at the journalists looking at him and he wondered if this was how people looked at men being taken to the gallows or the electric chair. One foreign correspondent came over to him to be friendly. He asked this man what he should make of Khomeini’s pronouncement. Was it just a rhetorical flourish, or something genuinely dangerous? “Oh, don’t worry too much,” the journalist said. “Khomeini sentences the President of the United States to death every Friday afternoon.”

On air, when he was asked for a response to the threat, he said, “I wish I’d written a more critical book.” He was proud, then and always, that he had said this. It was the truth. He did not feel that his book was especially critical of Islam, but, as he said on American television that morning, a religion whose leaders behaved in this way could probably use a little criticism.

When the interview was over, he was told that his wife had called. He phoned the house. “Don’t come back here,” she said. “There are two hundred journalists on the sidewalk waiting for you.”

“I’ll go to the agency,” he said. “Pack a bag and meet me there.”

His literary agency, Wylie, Aitken & Stone, had its offices in a white-stuccoed house on Fernshaw Road, in Chelsea. There were no journalists camped outside—evidently the press hadn’t thought he was likely to visit his agent on such a day—but when he walked in every phone in the building was ringing and every call was about him. Gillon Aitken, his British agent, gave him an astonished look.

He found that he couldn’t think ahead, that he had no idea what the shape of his life would now be. He could focus only on the immediate, and the immediate was the memorial service for Bruce Chatwin. “My dear,” Gillon said, “do you think you ought to go?” Bruce had been his close friend. “Fuck it,” he said, “let’s go.”

Marianne arrived, a faintly deranged look on her face, upset about having been mobbed by photographers when she left the house. She didn’t say much. Neither of them did. They got into their car, a black Saab, and he drove it across the park to Bayswater, with Gillon, his worried expression and long, languid body folded into the back seat.

His mother and his youngest sister lived in Karachi, in Pakistan. What would happen to them? His middle sister, long estranged from the family, lived in Berkeley, California. Would she be safe there? His oldest sister, Sameen, his “Irish twin,” was in Wembley, with her family, not far from the stadium. What should be done to protect them? His son, Zafar, just nine years and eight months old, was with his mother, Clarissa, in their house near Clissold Park. At that moment, Zafar’s tenth birthday felt far, far away.

The service at the Cathedral of St. Sophia of the Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain, built and lavishly decorated a hundred and ten years earlier to resemble one of the grand cathedrals of old Byzantium, was all sonorous, mysterious Greek. Blah-blah-blah Bruce Chatwin, the priests intoned, blah-blah Chatwin blah-blah. They stood up, they sat down, they knelt, they stood, and then sat again. The air was full of the stink of holy smoke.

He and Marianne were seated next to Martin Amis and his wife, Antonia Phillips. “We’re worried about you,” Martin said, embracing him. “I’m worried about me,” he replied. Blah Chatwin blah Bruce blah. Paul Theroux was sitting in the pew behind him. “I suppose we’ll be here for you next week, Salman,” he said.

There had been a couple of photographers on the sidewalk outside when he arrived. Writers didn’t usually draw a crowd of paparazzi. As the service progressed, however, journalists began to enter the church. When it was over, they pushed their way toward him. Gillon, Marianne, and Martin tried to run interference. One persistent gray fellow (gray suit, gray hair, gray face, gray voice) got through the crowd, shoved a tape recorder toward him, and asked the obvious questions. “I’m sorry,” he replied. “I’m here for my friend’s memorial service. It’s not appropriate to do interviews.”

“You don’t understand,” the gray fellow said, sounding puzzled. “I’m from the Daily Telegraph. They’ve sent me down specially.”

“Gillon, I need your help,” he said.

Gillon leaned down toward the reporter from his immense height and said, firmly, and in his grandest accent, “Fuck off.”

“You can’t talk to me like that,” the man from the Telegraph said. “I’ve been to public school.”

After that, there was no more comedy. When he got out onto Moscow Road, journalists were swarming like drones in pursuit of their queen, photographers climbing on one another’s backs to form tottering hillocks bursting with flashlight. He stood there blinking and directionless, momentarily at a loss. There was no chance that he’d be able to walk to his car, which was parked a hundred yards down the road, without being followed by cameras and microphones and men who had been to various kinds of school and who had been sent down specially. He was rescued by his friend Alan Yentob, a filmmaker and a senior executive at the BBC. Alan’s BBC car pulled up in front of the church. “Get in,” he said, and then they were driving away from the shouting journalists. They circled around Notting Hill for a while until the crowd outside the church dispersed and then went back to where the Saab was parked. He and Marianne got into the car, and suddenly they were alone. “Where shall we go?” he asked, even though they both knew the answer. Marianne had recently rented a small basement apartment in the southwest corner of Lonsdale Square, in Islington, not far from the house on St. Peter’s Street, ostensibly to use as a work space but actually because of the growing strain between them. Very few people knew that she had this apartment. It would give them space and time to take stock and make decisions. They drove to Islington in silence. There didn’t seem to be anything to say.

It was mid-afternoon, and on this day their marital difficulties felt irrelevant. On this day there were crowds marching down the streets of Tehran carrying posters of his face with the eyes poked out, so that he looked like one of the corpses in “The Birds,” with their blackened, bloodied, bird-pecked eye sockets. That was the subject today: his unfunny Valentine from those bearded men, those shrouded women, and that lethal old man, dying in his room, making his last bid for some sort of murderous glory.

Now that the school day was over, he had to see Zafar. He called his friend Pauline Melville and asked her to keep Marianne company while he was gone. Pauline, a bright-eyed, flamboyantly gesticulating, warmhearted, mixed-race actress full of stories about Guyana, had been his neighbor in Highbury Hill in the early nineteen-eighties. She came over at once, without any discussion, even though it was her birthday.

When he got to Clarissa and Zafar’s house, the police were already there. “There you are,” an officer said. “We’ve been wondering where you’d gone.”

“What’s going on, Dad?” His son had a look on his face that should never visit the face of a nine-year-old boy.

“I’ve been telling him,” Clarissa said brightly, “that you’ll be properly looked after until this blows over, and it’s going to be just fine.” Then she hugged her ex-husband as she had not hugged him since they separated five years before.

“We need to know,” the officer was saying, “what your immediate plans might be.”

He thought before replying. “I’ll probably go home,” he said, finally, and the stiffening postures of the men in uniform confirmed his suspicions.

“No, sir, I wouldn’t recommend that.”

Then he told them, as he had known all along he would, about the Lonsdale Square basement, where Marianne was waiting. “It’s not generally known as a place you frequent, sir?”

“No, Officer, it is not.”

“That’s good. When you do get back, sir, don’t go out again tonight, if that’s all right. There are meetings taking place, and you will be advised of their outcome tomorrow, as early as possible. Until then, you should stay indoors.”

He talked to his son, holding him close, deciding at that moment that he would tell the boy as much as possible, giving what was happening the most positive coloring he could; that the way to help Zafar deal with the event was to make him feel on the inside of it, to give him a parental version that he could hold on to while he was being bombarded with other versions in the school playground or on television.

“Will I see you tomorrow, Dad?”

He shook his head. “But I’ll call you,” he said. “I’ll call you every evening at seven. If you’re not going to be here,” he told Clarissa, “please leave me a message on the answering machine at home and say when I should call.” This was early 1989. The terms “P.C.,” “laptop,” “mobile phone,” “Internet,” “WiFi,” “SMS,” and “e-mail” were either uncoined or very new. He did not own a computer or a mobile phone. But he did own a house, and in the house there was an answering machine, and he could call in and interrogate it, a new use of an old word, and get, no, retrieve, his messages. “Seven o’clock,” he repeated. “Every night, O.K.?”

Zafar nodded gravely. “O.K., Dad.”

He drove home alone and the news on the radio was all bad. Khomeini was not just a powerful cleric. He was a head of state, ordering the murder of a citizen of another state, over whom he had no jurisdiction; and he had assassins at his service, who had been used before against “enemies” of the Iranian Revolution, including those who lived outside Iran. Voltaire once said that it was a good idea for a writer to live near an international frontier, so that, if he angered powerful men, he could skip across the border and be safe. Voltaire himself left France for England, after he gave offense to an aristocrat, the Chevalier de Rohan, and remained in exile for almost three years. But to live in a different country from one’s persecutors was no longer a guarantee of safety. Now there was “extraterritorial action.” In other words, they came after you.

The night in Lonsdale Square was cold, dark, and clear. There were two policemen in the square. When he got out of his car, they pretended not to notice him. They were on short patrol, watching the street near the flat for a hundred yards in each direction, and he could hear their footsteps even when he was indoors. He realized, in that footstep-haunted space, that he no longer understood his life, or what it might become, and he thought, for the second time that day, that there might not be very much more of life to understand.

Marianne went to bed early. He got into bed beside his wife and she turned toward him and they embraced, rigidly, like the unhappily married couple they were. Then, separately, lying with their own thoughts, they failed to sleep.

_17422494921.png )